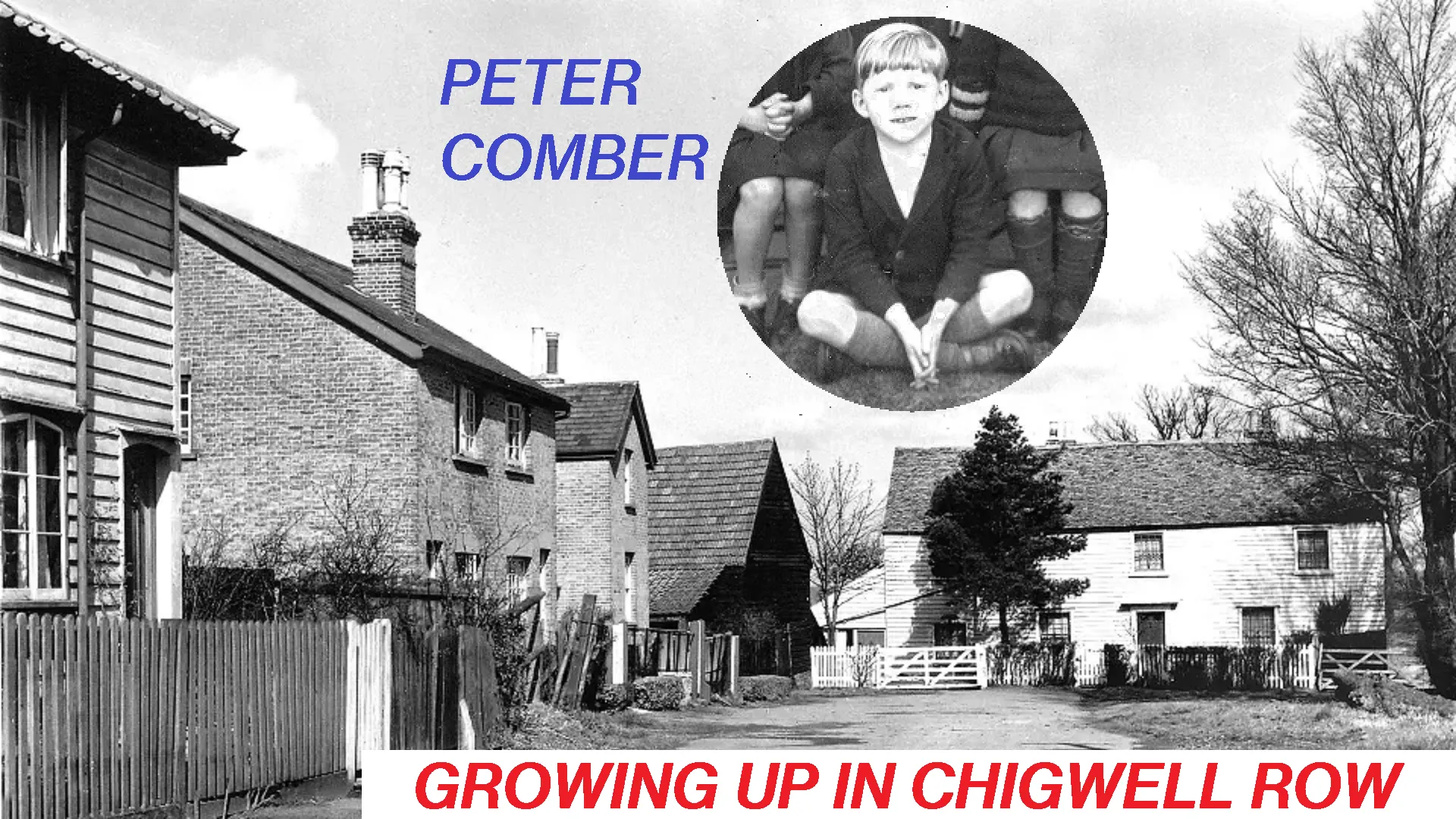

In 1930, the year I was born, Chigwell Row was still a somewhat rural village in South West Essex. Although situated a mere 12 miles or so from the centre of London there had been little change since Victorian times. Practically all of the 17th & 18th century wooden cottages and the later 19th century Victorian brick built houses in the village had outside toilets and were without bathrooms, although most had mains water laid on.

In ‘The Square’ at Lambourne End there were four wooden terraced houses with just one outside toilet between them! It was probably like this until well after the end of the war in 1945. (In the 17th and 18th centuries these cottages had to draw their water from wells!) Almost all had gas for lighting but there wasn’t any electricity, so appliances we now take for granted, like refrigerators, vacuum cleaners and washing machine etc. could not be used; anyway they would have, most probably, been too expensive for most people or were just not available. One cottage did have electric lighting though, Angel Cottage, just over the border in Lambourne Parish.

A postman by the name of Wally Faux lived there with his wife and three children. Wally was very practical and had installed a generator in a shed outside to supply his house with electric lighting. Before retiring for the night he would nip outside and turn off the petrol, the generator would then keep running on the fuel left in the carburettor to enable him to get back and in to bed before the lights went out; ingenious!

We did not have a telephone, not many houses did; but there was a public call box near the cross roads. When making a call you actually spoke to a person, an operator, who connected you to the number you asked for….eventually! To post a letter cost a 1½ d stamp or just over ½ p in new money! It went up to 2½ d (about 1 new ‘p’.) in 1941. Postage on post cards was 1d. Unsealed envelopes were also cheaper. Popular newspapers were, I think, 1d or 1½ d. Broadcasting was only eight years old in 1930 and television was still the stuff of dreams! In about 1936 we did have a new EKCO* ‘Wireless’, as radios were called then; nowadays you seldom hear a radio called a ‘Wireless’. Ours was a Bakelite art deco design in Brown and Cream; that ran off a rechargeable accumulator and a long lasting grid bias dry battery that heated the valves!

Sundays were always special and definitely a day of rest for nearly everyone. The vast majority of shops were closed, with only a few that sold ice cream, sweets or teas opening for a limited time. It was still the custom to wear our ‘best’ clothes on a Sunday and maybe go to morning service at ‘All Saints’ church and in the afternoon many of the children would go to Sunday school. Sunday lunch was always a ‘roast’ with, perhaps, relatives or visitors arriving later for tea in the afternoon.

Many of the folk in the village spoke with an Essex accent; an accent that is rarely heard nowadays, if at all, with the possible exception of one or two of the much older generation. In fact I can’t think of anyone who still does since Martha Lucas, Lil and Cyril Groves have died; Martha lived in a small wooden house (it’s no longer there!) next to the Two Brewers public house. The school children also spoke with an accent, apparently, but I didn’t realise that I had one until I was told I had an Essex accent when I started work. This is the genuine Essex country accent, not the awful ‘Estuary’ English that is often wrongly attributed to all of Essex!

The few Police cars and ambulances announced their presence by ringing an electric bell mounted on to the front of their vehicles. Firemen wore big brass helmets when driving to an emergency and rang the large bell by hand that was mounted high up on the fire engine.

Many local farms were still using working horses for jobs around the farm in the 1930’s, a time when horse drawn carts and carriages were gradually being replaced by motorised vehicles! I remember our milk being delivered by a horse drawn milk float; horses were still being used up to the early 1950’s by the United Dairies. Nowadays electric milk floats are used in those places where the milk is still being delivered in bottles!

There were still trams (that ran on rails) going through Ilford Broadway in the early 1930’s. Sometime later they were replaced by Trolley Busses that had two long arms on the top that were attached to wires that were suspended above them, supplying the power. The arms were always coming off at the junctions and had to be replaced by the conductor using a long hooked pole that was carried under the trolley bus for just that purpose. They ran between Barkingside and Ilford via Horns Road and across the A12 at the Green Gate to Ilford.

Our nearest train station was Grange Hill about a mile or so away; it was on the recently opened LNER (London and North Eastern Railway) line that ran to Liverpool Street station. The steam trains ran in a loop via Ilford and Woodford, travelling in both directions to Liverpool Street station. This line became part of the Underground Central Line in 1948 with the ‘underground’ trains running from Hainault to Newbury Park station above ground then underground to Gants Hill before emerging above ground again at Leytonstone. After Leyton it was below ground again into central London and beyond. The line from Newbury Park to Ilford was discontinued for passengers and was only used occasionally for freight. Central line trains ran a shuttle service over ground between the Hainault and Woodford stations. Before 1948, Steam trains ran from Liverpool St to Ongar via Woodford, but after the change to the London Underground Central line, the trains terminated at Epping.

The village did have a couple of bus services that operated earlier in the 20th century, so by the 1930’s getting to places like Ilford and Woolwich was possible. With one change of bus, Romford and London were easily reachable. I can just remember seeing busses with open stairs at the back! Those early busses had to use a very low gear to get up the hill to the Bald Hind when coming from Barkingside. On one frosty winter evening there was ice on that hill and the bus we were travelling on got stuck half way up, wheels spinning on the ice, we were not going anywhere, so Mum and me had to walk the next couple of miles or so to get home. We were well used to walking everywhere but we could have done without that in the dark at the end of a shopping trip to Ilford!

The first busses locally were independently run and very competitive with each other, but on 1st July 1933 they were all amalgamated to become London Transport. Of course being just 3 years old I don’t remember those independently run busses at all. The one bus that ran all week was the No. 25A bus. It ran from the yard behind the Maypole Public House in Chigwell Row to York Road in Ilford via Grange Hill, Bald Hind, Barkingside and Gants Hill. On Sundays and Bank holidays some continued all the way to London’s Victoria! Later it became the Number 26 bus. The service was discontinued sometime in the 1950’s when it was replaced by the No 150 bus. This ran a slightly different route from Chigwell Row to Ilford; going through the newly built Hainault housing estate before travelling on to Ilford via Barkingside and Gants Hill. The 101 bus only ran on Sundays and Bank holidays, travelling between Lambourne End and the Woolwich Free Ferry via Woodford Bridge, Wanstead and East Ham.

At holiday times and weekends in the summer, large numbers of people used to visit Chigwell Row and Lambourne End on these busses. They would, no doubt have come to visit the recently opened Hainault Forest that had been opened to the public in 1906 and to have tea at one of the many tea rooms that had opened up that were taking full advantage of the trade that came with all those visitors! Or maybe they just came to visit one of the three Public Houses in Chigwell Row, the ‘Maypole’ Inn, the ‘Retreat; and ‘The Two Brewers’ or more likely the popular ‘Beehive’ Public House at Lambourne End. Most of these Pubs catered for families by serving teas or meals of some sort. The Two brewers and the Retreat used to brew their own beer in earlier times and perhaps the others did as well.

The ‘Beehive’ public house was very popular because it was right on the edge of the Hainault forest. With the 101 busses from Woolwich and East London terminating at Lambourne End, Londoners could now easily get a taste of the countryside and the forest early in the 20th century. On a warm summer’s evening in the mid 1930’s I saw a large number of people queuing at the Chigwell Row cross roads waiting for a bus. A bus inspector was there to keep order and was assuring the queue that busses would soon be along to take them back to their destinations.

It wasn’t unusual to see competing ‘runners’ or ‘walkers’ going through the village particularly at holiday times. Ilford athletics club organised these from a long wooden building in the grounds of Carpenters Hall near the ‘Retreat’ pub. This ceased with the outbreak of war in 1939 and probably didn’t resume again after the war had ended.

Like most places within commuting distance of London, Chigwell Row has seen a great many changes since the end of the Second World War in 1945; housing estates have been built on the open fields in the village and on the estates of ten of the thirteen or so 18th and 19th century mercantile houses. With the exception of Clare Hall (irreparably damaged by a flying bomb in 1944), they had all survived the War but alas, not the developers after the war, when most of these large houses were demolished to make way for housing estates. The majority of these ‘merchants’ houses were on the north side of Manor Road, (now Lambourne Road) and mostly to the West of the crossroads in the village.

The only Public House that is left in the village now, is the Two Brewers, The Retreat went to housing at the end of the 20th century and The Maypole has been closed (2015) for over two years now, in spite of several attempts to reopen it. It will, no doubt, be pulled down in the near future to make way for housing of some sort. The wooden public house called, ‘The Beehive’ at Lambourne End was rebuilt in 1929, and eventually its name was changed to ‘The Camelot’; after further enlargement it became a ‘Miller and Carter’ public house.

I am not too sure but I have a vague memory of kerb stones being put in place in Chigwell Row village, probably around 1935/6? But it did have some street lighting though, with a few gas lamp standards scattered throughout the village. The cross roads at the ‘Maypole’ were single carriage roads without traffic lights; with so few motor vehicles traffic lights were unnecessary in the 1930’s. It wasn’t until well after the War had ended that electric street lighting replaced the old gaslight standards, and we had traffic lights at the crossroads with Romford Road becoming a dual carriageway.

The only open areas in Chigwell Row for people to enjoy nowadays are Hainault Forest and the 50 acre Recreation ground with its tennis courts and other sports facilities. About half of this area is still ancient woodland, a 25 acre remnant that was once part of Hainault Forest; it is a delightful walk in early spring when the Hornbeam trees are coming into leaf.

Chigwell Row’s southern border now adjoins the Greater London Borough of Redbridge with about half of the 800 acre Hainault Forest in Redbridge and a much smaller area in the Greater London Borough of Havering. The rest is in the Epping Forest area. Up until the creation of Greater London on 1st April 1965, both of these Greater London Boroughs had been in the County of Essex!

There cannot be many villages in Essex or any other county for that matter that have not seen a great many changes in the last 80 years; especially those that are within commuting distance of London or other large cities. The changes that have occurred in Chigwell Row since my childhood in the 1930’s are staggering, but there again I expect my parents and grand parents in Sussex would have said much the same in their day, but the changes would have no doubt, been at a much slower pace.

With such a large increase in the population and housing, Chigwell Row can hardly be called a village anymore. Sadly, the days when nearly everyone in the ‘village’ knew practically everyone else in the village have long since gone never to return! People are much more mobile now than they were in the early part of the 20th century.

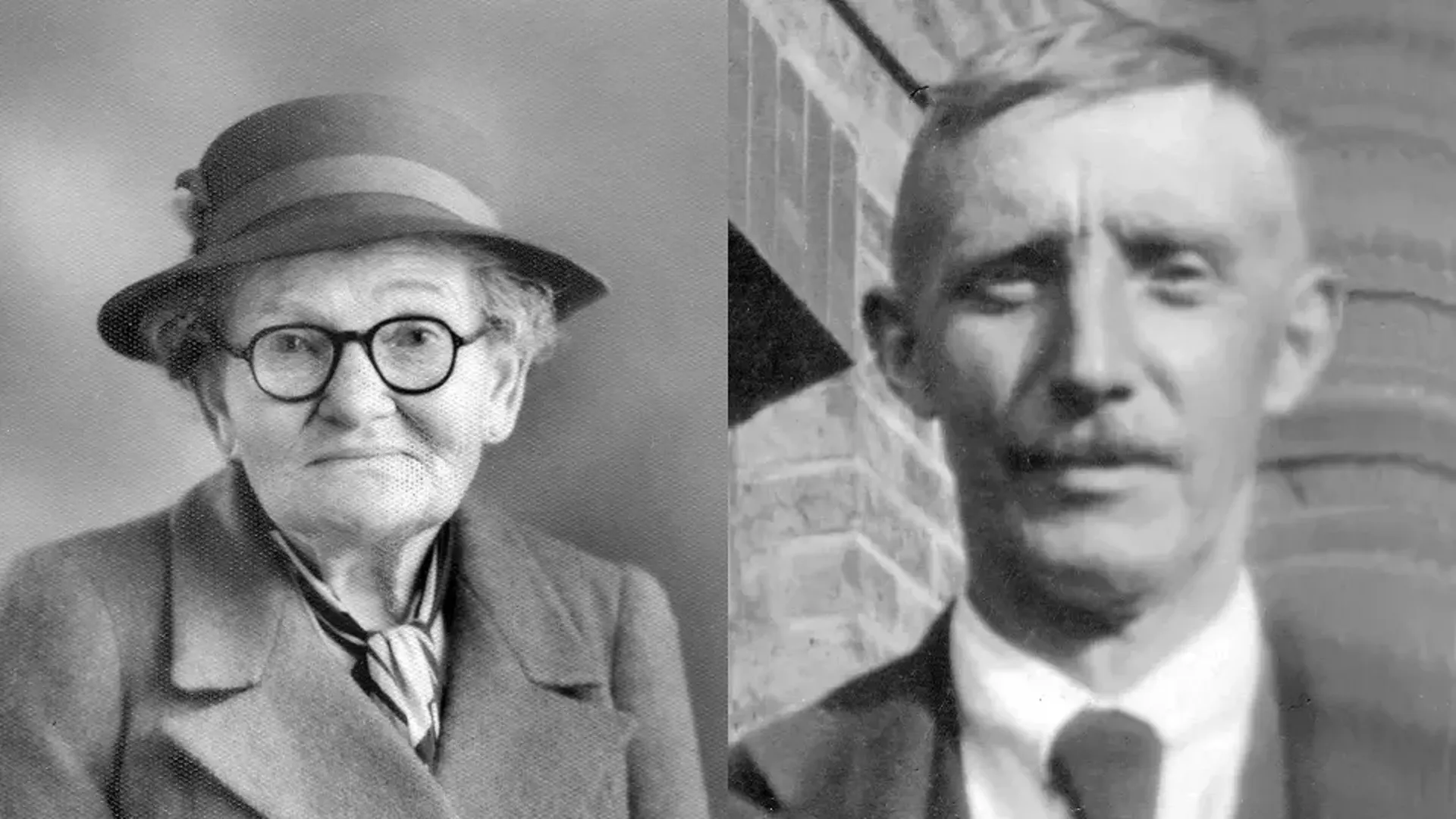

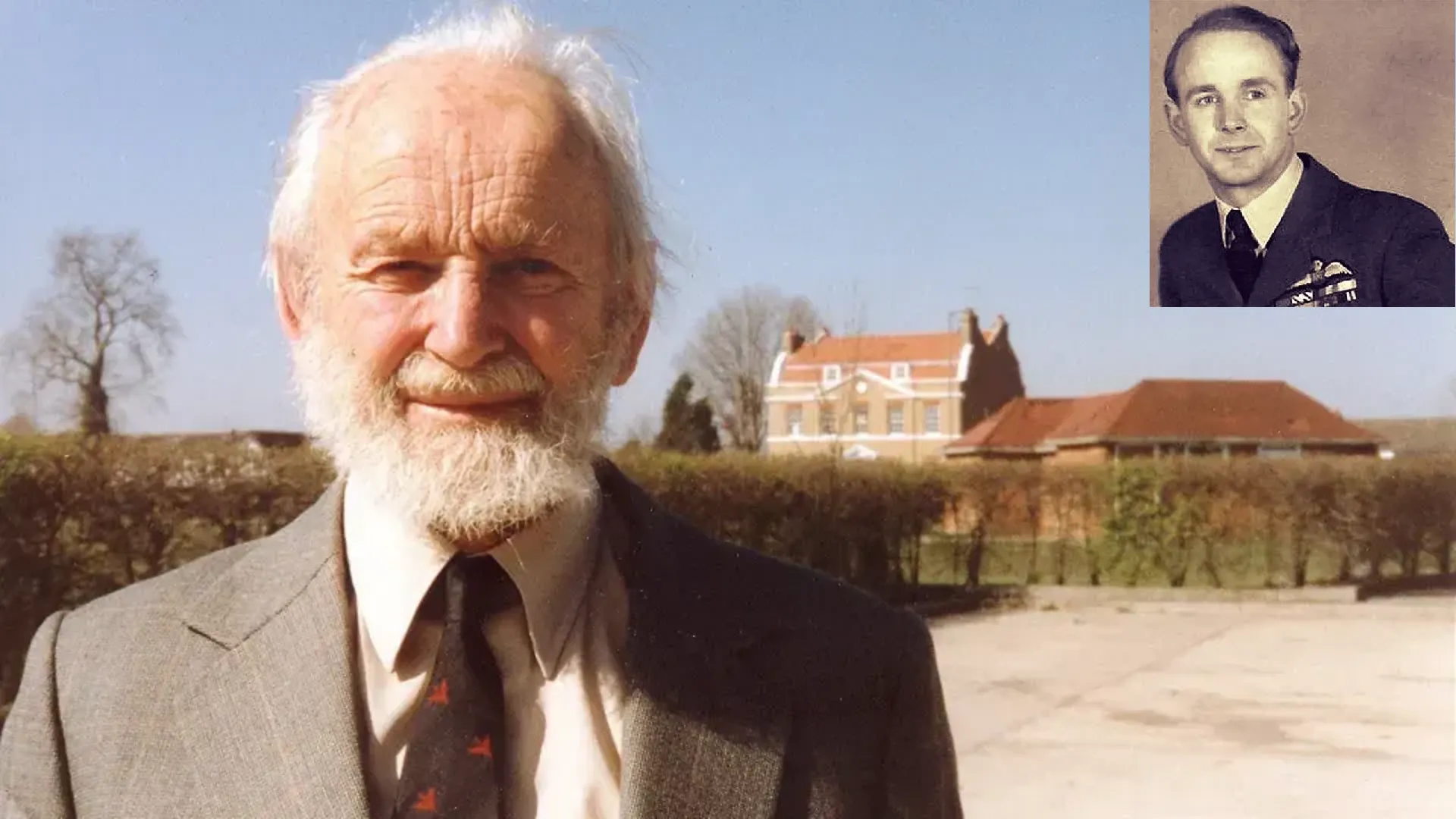

Having been brought up in West Sussex, my Dad in Monks Gate, Nuthurst and my Mum in Horsham; it begs the question how did my parents come to live in Chigwell Row in Essex and to leave such a lovely area in West Sussex? Well it happened like this: Dad was apparently apprenticed to a horse racing stable in Sussex; being small I think he may have had hopes of being a jockey. But at the age of 24 or thereabouts he left the stables; I don’t know why, he never spoke about it, but I always had the suspicion that he didn’t like it there, or perhaps he’d just put on too much weight to be a jockey, I just don’t know. He was courting my Mum at the time and was now out of work; that was until he saw a job advertised for a groom and chauffer that had a house that went with the job. He applied for it and got the job - with the Savill family (the Estate Agents branch of the Savill family) in Chigwell Row.

* Made at Southend-on-Sea by E. K Cole Ltd. ‘EKCO’, from Eric Kirkham Cole Limited.

Mum and Dad's wedding day

A hastily arranged marriage took place in August 1929, at Mitcham, I believe, (Dads older sister, Minnie lived there.) before moving into No1 Montfort Cottages, Grove Lane, Chigwell Row, Essex. 10 months later on the Summer Solstice, June 21st 1930, a Saturday, I was born an Essex man or rather an Essex baby boy! My mother always said it was the longest day of her life! Following the Wall Street crash a severe worldwide economic depression had started the year before I was born. (It was just a coincidence I had nothing to do with it!) The Great Depression, as it became known, lasted for a decade until the start of the Second World War in 1939.

The house my parents moved into was a three bedroom semi-detached late Victorian (c.1895) yellow brick built cottage with a slate roof in Grove Lane, Chigwell Row. The semi-detached Montfort cottages would have been built originally to house staff employed by the owners of Montfort House; a large early 19th century house off Manor Road a short distance away. Their extensive gardens were just a field away directly behind our house.

Having a brick built cottage with three bedrooms was quite a luxury when in the earlier wooden terraced cottages throughout the village, two bedrooms were usual. Electricity was unheard of but we did have some coal gas lighting in the three rooms downstairs. (Natural gas was not available in those days.) We had to take a candle in an enamel ‘candle-stick holder’ when we went upstairs to bed. The gas mantles that were used to provide our downstairs lighting at home were purchased from the Gaslight and Coke Company; that was the first shop on the right as you entered Barkingside High Street near the Fairlop roundabout. When the mantles were new they could be handled and easily put in place but, after the first lighting and the stiffening had burnt off, they were extremely fragile. It could be tricky when using a match or a taper to light the gas as just one touch and the fragile mantel more or less disintegrated and was unusable! Two chains hanging down from the fitting operated a lever which turned the gas either on or off, depending on which one of the chains you pulled. It was in about 1953 when we had electricity installed.

A large stone step led up to our front door. I really liked that step and used play on it when I was small, later it was ideal for sharpening my penknife! All boys carried a penknife in their pockets along with bits of string, marbles, elastic bands, fluff and other miscellaneous and unidentifiable objects! I don’t think it had ever occurred to any of us boys that a penknife could be used as an offensive weapon! (I think films and television have a lot to answer for!) Older boys in the Scouts even had sheath knives with a five inch blade! I still have my fathers Boy Scouts sheath knife with a deer antler handle complete with its leather holder from when he was a Boy Scout in about 1913 - 1918.

Like all cottages of that period the front door opened directly into the parlour, or the front room, as we called it; a room that we only used occasionally when we had relatives staying or at holiday times like Easter and Christmas. Our front door wasn’t used and was sealed up to keep the draughts out! It needed to be as older houses tend to be incredibly draughty.

In the front room was an upright piano that Dad had probably obtained from ‘Woodlands’ (later called Woodview!) In 2017 it was pulled down to make way for further housing. It had been the home of Phillip Savill until his death in 1922; he is buried in All Saints church yard.

Several pieces of furniture we had at home were items that had been discarded and were no longer required by the ‘Big House’. They were always very good quality as you would expect coming from a large and grand Victorian house. I tried and tried to play that piano without much success; I envied those who could play any tune on a piano by ear. I never had any lessons either, but I believe my younger sister did. I am not very musical but I used to play a portable ‘wind up’ record player we had. It played 78rpm records of which we had quite a few. I played and played those records and can remember many of the songs to this day, although I would have only been about seven or eight years old at the time.

A cast iron open fire was the only means of heating the front room; because of its only occasional use, it always took a long time for the room to warm up. A second room, next to the front room, was the Kitchen (nowadays it would be called the Living room!) where we cooked, ate, bathed and generally lived with its coal fired Range, or Kitchener as we called it, that burned almost continuously. It was allowed to go out about once a week or so, to allow the clinker that would build up to be removed, and any cleaning could be done.

Using the coal that was delivered and the wood we had collected meant that our chimneys ‘sooted up’ and had to be swept on a regular basis. A Chimney Sweep would be called and he would push his brush up the chimney from the Kitchener or a fireplace indoors. I was always posted outside to wait and watch for it to appear out of the chimney pot. When it did I would call out and then the Sweep would pull it back down taking the soot with it! Mum hated having this done as you can imagine it made quite a mess with soot everywhere indoors. The cloth the Sweep put up covering the fireplace was only partially successful in stopping the dusty soot escaping. The soot that was collected would be used on the garden or on the allotment but only after it had been well weathered over the winter to remove its acidity. Chimney fires were a serious hazard if you didn’t have your chimneys swept regularly! It was not unusual to hear of a chimney fire occurring somewhere or other in the locality; this was, apparently, always disastrous for the house and its furnishings if it did happen. It would make a dreadful mess with soot everywhere. We always had our chimney swept regularly so we never ever had to endure that trauma.

Mum always changed our curtains twice a year; it was normal and routine for homes in those days. The summer curtains were light and colourful but the winter curtains were heavier and often lined to provide some insulation to keep out the cold that came from those draughty wooden windows. With double glazed windows and much improved heating and insulation in modern houses it isn’t necessary to change your curtains twice a year and is rarely done nowadays.

The stairs that were off the kitchen divided the two main rooms. The cupboard that was under the stairs we used as a larder. A small porch off the kitchen led to the scullery and the back garden. Built in to the house was a narrow shed where dad stored the potatoes off the allotment, his garden tools, our bicycles and a long galvanised tin bath that hung on the wall. On Friday nights the bath would be taken down and used for our weekly baths. A brick built flush lavatory was tacked on to the outside of the house at the far end. We had to go outside to use it; no fun in the winter when it was cold or wet! We did have ‘proper’ toilet paper though, called Izal. It wasn’t very good, a bit like thin tracing paper and smelled of disinfectant. Each piece had a couple of lines of a nursery rhyme printed along the edge. For nights we had to use chamber pots - ‘Po’s’ or “Jerry’s” we called them.

The toilet had a rather ramshackle corrugated shed built around it where we kept the wood and coal along with a large hand operated mangle that Mum used for removing excess water from the washing on Mondays. Monday was always wash-day! It always seemed rather odd to me having a mangle in a shed where the coal was kept with all that coal dust around! When we had the coal delivered by Pearsons, the Lambourne End coal merchants, mother always counted the sacks as they went past the window! Pearsons coal depot was at Grange hill Station by the Western embankment.

As well as being suspicious, Mother was also superstitious! She would not have May blossom or an open umbrella in the house at any price, and she always made a point of kissing my Dad goodbye when he went to work whatever mood they might be in. She couldn’t bear to think that she hadn’t kissed him goodbye if anything untoward should ever happen to him at work.

We had to go through the coal shed to get to the lavatory that was tacked on to the outside of the house; the shed did offer some protection from the frost in winter but even so the lavatory’s lead pipes would occasionally freeze up causing them to split, especially if we forgot to light the small paraffin heater we kept in there for those very cold frosty winter nights. F. Harman & Sons the local builder’s and funeral directors plumber, Jack Harvey, had to come with his blow lamp and solder to ‘wipe’ the split pipe to repair it.

In the early days we had a cesspit near the front of the house that had to be emptied periodically. I remember the iron cover being removed and watching a tanker type lorry putting a flexible tube down into the cesspit and sucking the contents out! I made sure that I watched from a safe distance when this smelly operation was being performed! The sewage from the 17th century Millers Farmhouse at the bottom of the Lane ran down the fields in a deep smelly ditch probably from an overflowing cesspit!

In our scullery there was a shallow sink below a small window that looked out onto the backyard, it had a single brass cold water tap, with lead plumbing of course! In another corner of the scullery there was a brick built copper heated by a coal fire underneath with its own flue. A round, plain wooden lid sat on top. As well as being used for washing the laundry, the copper was used to heat up the water for our baths. On Friday nights the long galvanised ‘tin’ bath that we kept in the shed was brought indoors and placed in front of the Kitchener’s fire for warmth. It was partly filled with hot water from the copper before we all took it in turns to bath in the same water; it was topped up with more hot water as and when it was needed. Dad, mum, me, and later my sister; all washed in the bath.

Another Friday night ritual for me was ‘Senna Pods’, the pods were soaked in water to be drunk as a laxative. It was only given to me for some reason that I couldn’t understand; I say given, but actually I objected most strongly and had to be ‘persuaded’ to drink it because I have never smelled or tasted anything so foul or so disgusting in my life! I think it must have been a left over habit from my Parents child-hood, although my younger sister Pamela was never made to endure that laxative! I began to think that my sister was Dad’s favourite, especially after being made to give up my teddy bear to my baby sister. Years later this suspicion was further reinforced when my sister Pam used Dad’s can of petrol that he kept for his moped, on a garden fire that was dying down. A huge flash of flame frightened Pam and she dropped the can on the burning embers. Fortunately the petrol left in the can didn’t catch fire. When Dad came home I was the one that got into trouble; just because I had not retrieved his petrol can from the fire! I was more than a bit miffed over that I can tell you! Retrieving a can of petrol from a burning fire wasn’t, I didn’t think, a very wise thing to attempt!

In the kitchen was the black and shiny steel ‘Kitchener’ that we used for cooking and heating. It had a built in oven to the left of a barred fire which had two doors on it. A round plate could be lifted off the top above the fire for refuelling and a kettle or pot could be sat in the hole directly above the fire. A flue with a damper was embossed with the words, ‘The Clanick, Shoreditch E’. My mother regularly blacked the Kitchener with ‘Zebra’ Black lead and I think the shiny parts she brightened with a piece of emery cloth. The flat irons she used for ironing’ the clothes, were heated by standing them on the Kitchener. Checking that the iron was at the ‘correct’ temperature for ironing was with a wetted finger dabbed on to the sole plate! I don’t think it would have been too reliable if we had clothes made from man-made fibre at that time, that’s for sure! I’d guess Kitcheners were the forerunner of today’s much larger and modern Aga’s.

Sometime later, probably about 1938 I think, we had a gas stove with an oven and what a blessing that must have been for my mother. With its heat much more controllable it would have made cooking for her so much easier; it also enabled water to be heated up more reliably and certainly quicker. Later on we had a small ‘Ascot’ water heater that heated water only when you needed it. Safety Matches were used to light the gas stove and our gas lighting. Matches must surely have been one of the greatest inventions of all time. It certainly beats tinder boxes. (Or rubbing two Boy Scouts together!)

Cooking on the Kitchener must have been a work of art as you didn’t have very much control over the heat, but we ate a lot of suet puddings, all cooked on that Kitchener. The suet we used was bought from the butchers; a hard fat that had to have the skin removed from it and then be diced up finely and maybe put through a hand operated ‘mincer’. Steak and kidney pudding was a favourite; a basin was lined with the suet pastry and then filled with the meat, onions, carrots etc. and then topped with more suet pastry and covered with a cloth tied around the top of the basin with string. A ‘handle’ fashioned with the string across the top allowed it to be safely lifted in and out of the boiling water when it was cooked! It was cooked standing in a pot of simmering water for a very long time. Apple, Apple and Blackberry or Plum puddings were similarly made. Other puddings such as Golden Syrup (my favourite!), Jam Roly Poly, Spotted Dick, and others were all made using suet pastry and rolled in a cloth and tied at each end like a large sausage, before boiling or steaming.

Mother also used to make jam or syrup sponge puddings cooked in a basin. All served with ‘Birds’ custard of course. Bread pudding and bread and butter puddings were other favourites; both made from leftover stale bread. Nothing was ever wasted in our house! If we asked Mother what was for dinner or tea, she would always say; “Bread and pullet”But I never knew what that actually meant; and I doubt whether she did either. It appears to be attributed to several Counties especially East Anglia although my Parents came from Sussex. Its meaning is unclear but it seems that it may have meant that you tied greased bread to a piece of string before swallowing it and then ‘pulling it’ back again for reuse! Ugh!

There was always a basin of beef dripping kept in the larder under the stairs to use on our toast. The bread was toasted on an expandable toasting fork in front of the Kitchener’s fire and the dripping with its savoury jelly was then spread on to it. It was very tasty! During the War when we had rationing*, Beef dripping would have eked out the fat ration. It would have probably been used for frying some things like Bubble and Squeak – absolute heaven! (Fried left-over cooked potatoes and vegetables.) Also in the larder there was always a bottle of ‘Camp’ coffee; a syrupy mixture of coffee, chicory and sugar. A teaspoonful was put in a cup and hot milk or water with tinned, sweetened condensed milk added – but not to my young taste! (I liked sweetened condensed milk though, and liked to dip my finger in an opened tin!) Everyone seemed to use ‘Camp’ coffee then, as the instant freeze dried coffee wasn’t available until well after the end of the War.

Another product we always seem to have, was Salmon and Shrimp Paste, it was spread onto bread or in sandwiches; it had a pleasant but fairly strong fishy flavour. I’d guess it was cheap to buy and economical to use; it is still commonly available today. Libby’s Evaporated milk (Milk with about 60% of the water removed; it was only available tinned), was a milk product we used instead of cream. It was the consistency of single cream and came in tins. It had a distinctive taste of its own, different to fresh milk, not unpleasant; but it made tea…undrinkable! Without a refrigerator we couldn’t keep fresh cream for very long.. Milk was not pasteurised and only available as full cream milk – straight from the cow! In the early days I believe Dad got our milk from the farm that was behind ‘Woodlands’ - Phillip Savill’s large Mid Victorian house. It wasn’t unusual for these large houses to have their own adjacent farm, supplying the house with milk, butter and meat etc. Sometimes in the winter, the milk tasted pretty foul; it was apparently because the cows had been fed on mangolds (mangel wurzles) – a type of root vegetable.

Early in the war I can just remember our milk being delivered by A & E. Winter of Limes Farm in Chigwell. (Shortly after the war the farm house was pulled down and the Limes Farm housing estate was built on the site of the house and its farmland.) Later on our milk was delivered by the United Dairies horse drawn milk float, it came in ½ pint, 1 pint or quart (2 pints) sized returnable glass bottles; it also gave us a ready made local delivery service - Les the milk-man! He would deliver messages or small items etc. between the customers that were on his milk round!

If you needed to keep the milk for more than a day or two especially in the summer, you had to boil it in a milk saucepan to prolong its life; it ensured that it didn’t go ‘off’ for several days! The milk saucepan was in fact two saucepans, one sat half in and on top of the other. Water was boiled in the bottom one to heat the milk in the top, it meant that the milk didn’t burn or boil over. When the milk cooled a skin would form on the top of the cream that I liked to put on my breakfast cereal. We never had refrigerators of course.

What a nightmare this way of living would have been for modern day nutritionists! And yet amazingly there was hardly any obese children in school (There was one, who always had a runny nose; she was always falling asleep in class!), without cars they presumably burnt it all off by running about and walking to school. At home, we ate plenty of vegetables as well, off Dads allotment. I was always made to eat my ‘greens’! Ugh! Small children do not like greens! I always had to finish my main course as well, before I could have any pudding! (I am not too sure that this was a particularly good idea as it probably encouraged over eating!) Eating meals was always sitting around the table together as a family and we were never allowed to leave the table until everyone else had finished eating. Walking about eating was a definite no-no. We had a high chair that converted into a rocking chair. The two front legs were curved forward and the back legs were curved backwards, each leg had a metal wheel. By releasing the locked legs the chair lowered into a rocking chair. It was quite ingenious, but very heavy and probably Victorian. I would have used it but I can only remember my sister in it; it was just used as a high chair, never as a rocking chair. I don’t know how my parents came to have such a chair, but it was most likely another item that had been discarded by ‘Woodlands’ the house where dad often worked.

Fruit, including soft fruit, was plentiful but only when it was in season and was mostly sourced locally. At Christmas the mincemeat and the Christmas puddings were all made at home. (Suet was used in them, of course.) Small silver thrup’ny joeys - 3d pieces - were put into the puddings for luck! If anyone got one (I think it was always arranged that I got one!) in their pudding on Christmas Day, you had to make a wish. Afterwards we were expected to give them back to Mum for reuse in a year’s time as they were no longer being minted. (They were last issued in 1922. I have inherited several of them some dating from Queen Victoria’s reign.) We always had a large chicken on Christmas Day. I don’t think having a turkey at Christmas was very popular among the working classes until much later. In those days, having chicken to eat was a luxury that we only had at Christmas or perhaps Easter; they were generally unavailable or most likely too expensive for us to regularly buy them at other times of the year. Nowadays of course, chicken is one of the cheapest of meats that you can buy and good value for money.

Jams were made as the various fruits came into season and a lot of fruit was bottled in Kilner preserving jars for future use. Runner beans were preserved in stoneware jars. A layer of prepared beans then a layer of salt and so on alternating until the jar was filled with a final layer of salt. I can’t say it was very successful; the beans were always very soft and more often than not, rather salty when eaten!

The cooking salt we used came in a block that had to be carved up into small pieces and broken down with a rolling pin before it could be used; that was usually my job! In those days there just wasn’t any other method of keeping food; there were no freezers or refrigerators in the average domestic home. Although we didn’t have electricity there were gas operated refrigerators available, but we didn’t have one. When I started to crawl I used to go backwards; or so I was told. Not having ‘eyes in the back of my head’ was a big disadvantage! Dad said he got me to crawl forwards by placing a piece of chocolate a few feet in front of me. I promptly crawled forwards and never crawled backwards again!

Upstairs there were three bedrooms with a double bedroom either side of the small square landing at the top of the stairs and a small bedroom leading off the central double bedroom. This central room was always my parents. It was in this room that both my sister and I were born, assisted by the local midwife Nurse Guys. She cycled everywhere from her house in Vicarage Lane; she was the midwife for all the mothers in the area when they were giving birth. No hospitalization for pregnant mums about to give birth in those days! I had the small bedroom that led off from my parent’s bedroom until I was about eight or nine years old. It was when my sister outgrew her cot and needed a proper bed that I was moved into the front bedroom. Mother was scrupulously clean and always examined the bed linen for signs of bed bugs – small spots of blood I believe; but I don’t recall her ever finding any! I guess that might have been a problem for some households in those days. She was also a fresh-air fiend; the bedroom windows would be opened wide on most days, even in winter. She always got up very early at about 6 am, and would bring me up a cup of tea to wake me up for school. There would always be grouts left in the cup so I used to throw them out of the open bedroom window into the field outside, until one day I ended up with just the handle in my hand; the cup had gone as well as the grouts! I was in big trouble especially as my parents refused to believe my story, but it was perfectly true, the cup had separated from the handle and ended up in the field outside!

The Kitchener was the only source of heating that was used in the house. Although each bedroom had its own cast iron fire place, I can’t remember them ever being lit so the bedrooms were always very cold in the winter; on frosty nights the windows would freeze up on the inside, with beautiful leaf and fern patterns on them by the morning. Hot water bottles were an absolute necessity during the cold winter nights. They were either the usual rubber sort with a woollen jacket, or the hard ‘stone’ water bottles, triangular in profile; in the morning the water would still be slightly warm so it was used to wash with! That’s recycling at its best!

After I was toilet trained a potty was kept under the sink in the scullery for me to use. Later on it was taken away and I was expected to go ‘out the back’, but I didn’t, I still went under the sink – potty or no potty! Well I guess I would rather than having to brave the elements to go to the toilet outside, especially at the tender age of about two or three. I don’t really remember the incident but I vaguely remember getting my legs slapped very hard one day and being sent to bed! Just going “Out the back” was an expression we always used in our house when needing to use the ‘flush’ toilet that was brick built on the outside at the end of the house.

* The first items to be rationed for each person per week were:-

Bacon (or ham) 4 oz’s,

Sugar 12oz’s (At the end of summer extra sugar was available for Jam making.)

Butter 4 oz’s (although this amount varied from time to time according to supply.)

Meat was rationed at 1/10d worth a week on 11th March 1940 (about 1 lb in weight.) This was later reduced to 1/2d and had to include canned beef.

Tea 2 oz’s.

Margarine, cooking fats and cheese 2 oz’s were added in July.

Cheese was reduced to 1 oz the following May. (Cooking fats were reduced to 1oz in 1945!)

In the following March, Jams, Honey and Lemon curd and the like were rationed. It varied between 8oz’s and 2lb per month.

Sweets or chocolate was 4oz’s per week.

Woolwich Free Ferry

I liked it when relatives came to stay with us, mostly before the start of the Second World War in 1939. Both Dad’s sisters used to visit us fairly regularly. Minnie, dad’s older sister with her husband George came from Mitcham to visit once or twice a year, and sometimes came with their daughter, also a Minnie, but for some reason was always called ‘Nibby’; she would come with her boyfriend Cecil. Dad’s younger sister, my Auntie Amy and Uncle Dave, came more often as they only lived at Woolwich; a short journey to the Woolwich ferry to cross the Thames and then the 101 bus to Chigwell Row. Uncle Dave worked at the Woolwich Arsenal until he was called up at the beginning of the war in 1940 to serve in the Royal Army Medical Corp. When they stayed with us I would climb into their bed in the mornings when Auntie Amy would tell me a traditional fairy story such as Red Riding Hood or Goldilocks and the three bears. She was very good at story telling.

Without the distraction of a television, the adults often played card games, especially Cribbage; or they would play Darts. Our Dart board was in a shallow box with two doors that when opened up wide were black on the inside, on which we chalked the scores. It was a permanent fixture mounted at the top of the ‘Kitchen’ door.

I can remember Uncle Dave and Dad experimenting with photography in about 1936-7. They produced contact prints by exposing the light sensitive paper to our gaslight in a frame that sandwiched a negative and the paper together; then processing them behind a thick cloth stretched across the alcove on the left of the chimney breast in the kitchen. I can’t remember how successful it was as they wouldn’t let me ‘help’! The wet prints would be pegged out on a makeshift line to dry. Perhaps my photographic ambitions were started back then!

Dad’s older sister Minnie came with her husband George to visit us from Mitcham, travelling on the London Underground and then on the LNER steam train from Liverpool Street Station. They were always welcome as far as I was concerned as Uncle George always brought with him a good selection of comics from ‘ Marshalls’ the Newspaper and Magazine Wholesale Company where he worked. As a bonus I always got comics a week or two before they were available in the shops!

We sometimes visited Uncle Dave and Auntie Amy at their home in Woolwich, usually just for the day. We would catch the 101 bus that took us to the Woolwich ferry. We would then board one of the ‘steam’ driven Free Ferries and cross the Thames. I loved Dad taking me down into the engine room with its lovely smell of oil and steam and watching the polished brass, copper and shiny steel machinery churning away; backwards and forwards.

On one of our visits to Woolwich, I had my hair cut for the very first time at the age of about 3; it was long, blond and curly. The barber’s shop, recommended by Uncle Dave, was, I believe, in Shooters Hill, where I remember the barber placing a plank of wood across the arms of the barbers chair for me to sit on. (I was just too small for the chair; the barber would have found it difficult to reach down to me!) I believe my Mum may have had a few tears, but as far as I know, none of my curly locks were kept.

Very few people had a television set before the war, as it was the very early days of television broadcasting, but Uncle Dave had one; I think it was a Marconi television. Early in 1939 I remember we all watched a live Eric Boon boxing match on a very small 9” screen; it was in black and white, of course. Their house and all their belongings including the television were badly damaged or destroyed by a bomb during the blitz in 1940. The fight was Eric Boon’s (nicknamed the Fen Tiger) defence of his British Lightweight title fight against Arthur Danaher on the 23rd February 1939; it was the first live television broadcast of a boxing match. Boon won on a technical knock-out in round 14.

The BBC Television Service started its regular broadcasts from Alexander Palace on 2nd November 1936. It was discontinued on 1st September 1939, 2 days before War was declared, and did not resume broadcasting again until the 7th June 1946.

Auntie Amy and Uncle Dave with mum’s younger sister, Auntie Alice would often spend Christmas with us; it was always a fun time with party games in the front room. Without any television to watch or distract us, we had to make our own entertainment in the 1930’s. Christmas presents (from Father Christmas of course!) would be opened in great anticipation; Dad always received a decorative tin of tea from Savill’s his employer. (Tea was an expensive and valuable commodity in much earlier times!)

I received a wooden Fort one year with lead soldiers who always seem to eventually lose their heads! Match sticks were used to try to hold the heads back in place but it wasn’t very successful. I found out that lead tastes quite sweet if you lick it; but I don’t think it was realised in those days that lead was quite so poisonous! Goodness knows how much lead I may have ingested.

One Christmas I received a cut-out book of the Cunard Ocean Liner RMS Queen Mary for me to cut out and assemble. The ship had been launched a few years earlier in 1934. Ironically, just before the war started in 1939, I had a German made Shuco clockwork model red sports car for Christmas. It was a wonderful piece of engineering; it had 3 forward gears, neutral and a reverse gear, with a clutch on the outside of the body. If I still had it complete with its box it would be worth about £300 now according to a recent Antiques Road show programme. My parents had paid 5/- (25 new pence!) for it; that was an awful lot of money for them in 1938, being about one eighth of Dads weekly income.

Like most children I had a favourite teddy bear, but after my sister was born on 21st April 1937, I had to give my teddy to my baby sister. My Parents considered I was too old at seven or eight to have a teddy bear so I was made to give him up, with much protesting, to my baby sister. I was very upset at the time. Too old at seven, good heavens; you are not too old at seventy to have a teddy bear! I don’t think I was ever quite the same after that!

Although my sister was born on April 21st 1937 at home like I had been nearly seven years earlier, I can’t remember her actual birth. But it would have almost certainly been during the Easter holidays when I spent two or three weeks staying with my Auntie Amy and Uncle Dave in Woolwich; I was two months short of my seventh birthday, and it was my first time on my own away from home so I had a few tears on the first night! In the days that followed she took me to the Tower of London and the Imperial War Museum and many other places of interest in London. She also showed me the Fire station not far from where she lived at Woolwich and we looked at the two lovely bright red and polished brass fire engines that were there. It was then, at the age of almost seven, that I decided that is what I wanted to be – a fire fighter. I never was but my maternal Grand Father had been in the Horsham fire brigade, and my father joined the fire service soon after the outbreak of the war in 1939. So I suppose you could say it was in the family!

Like many men Auntie Amy’s husband Dave smoked; ‘Piccadilly’ brand cigarettes were his preferred choice – but not where he worked, of course, at the Woolwich Arsenal! Uncle Dave was slightly built but he had very strong arms and his hands were always stained yellow from the explosives he handled and probably from the smoking of his cigarettes as well! He suffered with emphysema in retirement and old age which made him very short of breath.

Grove Lane where Peter Comber lived

Although it is only about 200 yards long, Grove Lane only had houses on the left hand side towards the bottom end of the lane in the 1930’s. A brick built Victorian detached house was the first, followed by Grove Cottages, a row of 9 wooden terraced 18th century ‘2 up and 2 down’ cottages (Note; There are now ten terraced cottages, an extra one was sympathetically added on the R/H end several years ago!) An entrance to the fields behind the houses separated the Grove cottages from the semi-detached Montfort Cottages. We lived in the first of these two cottages. A single brick cottage followed with several old wooden farm buildings right at the end with the early 18th century wooden Millers Farm House right across the bottom of the Lane. I can just remember seeing cattle in those farm buildings, probably in 1934/5. They were not used after that for over 30 years before eventually succumbing to a new development. The lane was a fairly close knit community; as once moving into one of the cottages it was seldom that anyone moved again. They stayed where they were for the rest of their lives.

Nobby Tridgett was quite a character. He moved into No 1 after his elderly relatives, a Mr and Mrs Tridgett who lived there had both died by the late 1930’s. Nobby had a high built up boot for his short right leg which gave him a strange gait so he went everywhere by horse and cart using ‘Billy’ his feisty grey pony with either his two wheeled or his four wheeled cart. He liked his drink did Nobby. One day when he was leaving the Retreat pub he offered to give two large ladies a lift, as they got to the slope by Scotts cottages the weight was too much and the cart up-ended and they all fell out of the back. Mrs Green in Scotts Cottages gave them all a cup of tea to get over their shock. On Sundays Nobby would go to the Maypole pub and get drunk. After closing time he would rely on Billy his pony to get him back home in Grove Lane! Nobby kept his horse and carts in the field behind our house. The trouble was that once ‘Billy’ got going it was difficult to stop him. He would go sailing passed the top of the Lane and way up the road before Nobby could bring him to a halt. Nobby would eventually get him back and into Grove Lane where they would career down the Lane at break-neck speed, swinging round into the field between our house and the wooden cottages and then charge around the field several times like a Roman chariot, before eventually stopping. It was quite amusing watching him; but how Nobby managed to stay on the cart without ever falling off or the cart turning over I’ll never know. It was our Sunday afternoons entertainment! (Or perhaps he did fall off sometimes!)

I broke a window in No 2 Grove cottages bedroom window on one occasion; a spinster Lily Vale lived there. I had made myself a parachute and on the end was a cardboard canister into which I had put a large stone. The parachute was launched by swinging it around my head and letting go. On this occasion the box spilt open and the stone carried on and headed straight for that upstairs window in No.2, Oh dear! I was in trouble.

The Haddons lived at No 5 in the cottages and were particular friends of ours; we were the only two families in the Lane with young children. Mr Haddon was the only man in the Lane to own a motor car; I think it was a Morris car that had a dickey seat at the rear. A Dickey seat was an uncovered seat that opened up from the rear of the vehicle (Where the car boot would normally be on a modern car!).

At No 6 lived the Sheldons, a couple without children; they just had a dog called Bimbo. One day Mr Sheldon went missing, no one knew where he was or where he may have gone. His wife had no idea where he was and was very worried. After much searching I believe it was Mr Haddon who found him, hanging from a tree in the copse behind the houses; he had committed suicide, what a terrible shock. As you can imagine there was a lot of speculation and gossip as to how he may have become so depressed that he would want to take his own life.

Lily Vale’s brother, Bill, lived at No 8 with his wife. Bill was a Road sweeper by trade, they didn’t have any children of their own, but just before one Christmas in 1937, Bill took me to Ilford on the bus and bought me a Christmas present. A nice surprise!

In the fields that belonged to Frog Hall on the right hand side of the Lane opposite Grove Cottages, there were quite a few old horses that had been retired from the United Dairies milk float duties. (I believe the Ex-Chairman of the United Dairies was living at Frog Hall at the time.) In the hot weather the horses would all gather under the shade of a large Oak tree in the centre of the field, just quietly dozing and constantly flicking off the tormenting flies with a swish of their tails or a shake of their heads and manes.

Two unmarried well educated and very religious sisters were living in Millers farmhouse when I was young; Millicent and Irene Mawer. (They had a nephew who was the Chairman of the London Development Agency in its early days.) Millicent was the eldest and stayed at home while Irene worked at the British and Foreign Bible Society. I used to get foreign stamps from her. Collecting British, Colonial and Foreign stamps, was a hobby widely pursued by many of us boys!

Millicent cooked a lot and baked her own bread; she would often ask me to cycle into the village and collect yeast for her from Sharpes the bakers. I rather liked the taste of it so I would pinch a tiny bit on the way back home. It came in a greyish lump with the consistency of soft cheese; live yeast I suppose. I usually got 3d (just over 1p) or a piece of homemade cake for collecting it, so I didn’t mind going on that errand.

Throughout the war Millicent held prayer meetings once a week in the farmhouse to pray for the war, but not everyone in the ‘Lane’ went to them. Millicent and her sister Irene were Church of England, but evangelical, so there was a certain amount of conflict with our local vicar I recall, but I never really understood it. I just couldn’t see what the problem was; after all we were all Church of England. They were known to us, affectionately, as the Happy Clappy Brigade. This was further reinforced when Mum, me and some of the other residents from the ‘Lane’ went with the two Miss Mawer’s a couple of times to somewhere in East London I think it was, where we all took part in a lively service held in a hall and listened to a lively and engaging sermon by a Mr Medley!

Millicent used to set me challenges by giving me verses and psalms from the Bible to find and learn off by heart.. I can only think she thought it would be a good way of getting me used to regularly reading the bible. In later life it hasn’t worked too well I am afraid to say! I still have the leather bound bible the two sisters gave me as a wedding present in 1955! Sometime afterwards in the 1960’s, the two sisters retired and moved from Chigwell Row to be nearer to their niece in the Wirral in Cheshire. Millicent the elder sister died not long after they moved, but Irene continued living in the Wirral for several years.

Oaklands Terrace Cottages early 1930’s

SHOPS AND OTHER SERVICES

Chigwell Row was fairly well off for shops when I was young. You could buy almost anything except for clothing and new furniture. The shops didn’t open on Sundays, as it was against the law and Thursdays was early closing with the shops only open in the morning. This was normal throughout the country although the early closing day varied from area to area; but it was always midweek - usually a Wednesday or a Thursday.

And at the far end of the shop was the Post Office counter that was run by the manager’s daughter, Hilda. My mother’s weekly grocery bill from there always came to about 14 shillings a week or 70p in new money! The groceries were delivered on Friday nights by Pardey and Johnson’s van. The driver, Bill somebody or other, I can’t remember his full name, ran off with the manager’s wife; as you can imagine it was the talk of the village. But it must have been acutely embarrassing, for the manager Mr Wilding.

There were two doctor’s surgeries in Chigwell Row. Our family doctor, Dr Ellis, came once a week from his practise at ‘White House’ in Abridge. His surgery was held in the front room (parlour) of the end house of Oaklands Terrace cottages next to Pardy & Johnson’s General Store. The front door opened directly into the front room so you had to wait outside until it was your turn; not so good if it was wet or cold! Inside, the room was very Victorian - complete with an aspidistra and a fringe around the mantle shelf! Later he transferred to one of the Victorian brick built terraced houses on the right hand side in Gravel Lane, where you waited in a very narrow passage for your turn to see him; at least you would be waiting in the dry if it was raining. Dr Ellis was a great one for visiting the sick, often visiting on Sundays and Bank holidays! Any medicines required were made up by the Doctor himself at his Abridge surgery.

The other Doctor who had a one day a week surgery in Chigwell Row was Dr Pratt from Chigwell. His surgery was held in Socketts Hall. (Socketts Hall has since been replaced by a much larger property.) Dad always used him as his doctor because of his employment with Savill’s, as Doctor Pratt was married to one of Phillip Savill’s daughters, a sister to Dad’s employer, Miss ‘Winnie’ Savill. Whenever Dad was prescribed medicine, it always seemed to contain quinine; I can only presume the good Doctor reasoned if it tasted awful you would think it had to be doing you good! Good psychology that! It became a standing joke in our family.

There were two shops, one in each of the two blocks of four ‘Oakland’s Terrace’ cottages, one was the newsagents and tobacconist shop - Dellow’s. Mr Dellow delivered the papers himself throughout the village on his bicycle, although I never saw him actually riding it, he would always seem to be pushing it with the newspapers in a bag slung over his cycle cross-bar. In the winter he always had a drip on the end of his nose; it seemed to be there throughout the winter! I used to wonder if it would develop into an icicle in frosty weather! He always reminded me of Mr Punch with his ‘hooked’ nose! In his shop he sold things like cycle parts, batteries, sweets and fireworks for November 5th. Dad always bought our batteries and our fireworks from Dellow’s shop. November the fifth was an exciting time as we always had some fireworks! The War put a temporary stop to that annual event!

We had the Daily and Sunday Express newspapers delivered by Mr Dellow. Every day I would look forward to Dad reading to me the adventures of Rupert Bear from the paper; that was until I was about seven years old and able to read it for myself. Mickey Mouse Weekly was a colourful comic I had delivered for many years; with Mickey and Minnie, Goofy, Donald Duck with his mischievous nephews and all the other Disney characters and stories like Pinocchio and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs etc as a series of cartoons.

In the other block of Oakland’s Terrace cottages adjacent to Dellow’s shop, was ‘Fuller’s’ tea rooms. Later on it sold second hand furniture and antiques of a sort. Between these two shops was a wide path that led to stables, where the horses had been kept for the Hackney carriage business run by the Green family. Eventually, motorised transport replaced the horses. ‘Stump’, the village tramp was quite a character; he used to sleep with the pigs in the pigsties further along the village close to the garage with its single petrol pump,. He walked awkwardly with the aid of a stick; he was a soldier in the Great War and got his injuries serving in France. (His real name was Smith!) Eddie Green used to cut his hair with horse clippers and put racing bets on for him. Some of the children used to poke fun at him and he would shout and wave his stick at them. The present ‘Lambourne News’ shop was just a sweet shop when I was young; it was at one time called ‘The Doves Nest’, but I only remember calling it ‘Reads’ - run by two sisters, the Miss Read’s and their bachelor brother. It was a lovely shop; early in my life you could buy sweets for as little as a farthing, but mostly it was a ha’penny or a penny. A quarter (4 oz.) of good quality sweets, like acid drops or pear drops, was 3d or 4d. (Less than 2 new pence!) Shortly after the two sisters retired to live in Grove Lane, the shop’s new owners took over the Newsagents business from Dellow’s shop which had closed after Mr Dellow’s death.

There were three tea gardens and several smaller tea rooms throughout the village and several at Lambourne End that sold cold drinks and teas, all catering for the large number of visitors that came from East London on the busses at weekends and holiday times. Sunnymede tea gardens served their teas from a First World War railway carriage at the side and to the rear of the petrol garage. I wonder how they got the Railway carriage to there? (At the end of the First World War, ex Army railway stock was sold off cheaply to ease the housing shortage!) Opposite the Two brewers Pub was Bliss’s tea Gardens and a kiosk that sold ice cream, with an invitation to ‘Come across for the finest ice cream you have ever come across’. Without electricity, blocks of ice were delivered to make and keep the ice cream cold. Walls ice cream was sold from a tricycle with a large ‘keep cold’ box with two large wheels, one on either side; with a single wheel at the rear. ‘Stop me and Buy one’ was the slogan on the ‘keep cold’ box.

Opposite were two semi-detached shops built in 1903. The right hand one was the bakers; where everything was baked on site. (And still is!) Hot-Cross buns were delivered by the owner Tommy Sharpe in time for breakfast on Good Friday morning cost ½ or 1d each! I did a few deliveries in 1944/5 for him, using a bicycle with a small wheel and a large basket at the front, just like the one Granville used in ‘Open All Hours’. When I returned Tommy Sharpe would pay me and give me a hot freshly baked doughnut rolled in castor sugar from the bakery behind the shop. Absolute heaven! He wanted me to do his deliveries on a regular basis but I had started work by then as an apprentice at Henry Hughes and Sons Ltd and could not help him.

I believe Mum bought Petit Beurre and Arrowroot biscuits from the Bakers, probably because they were better value for money - you got more of them to the pound! They came in fairly large square tins and were sold loose. When the baker got to the end of the tin the broken biscuits left in the bottom were usually sold off a bit cheaper. If we did have cream or chocolate digestive biscuits and tinned salmon, which I particularly liked, (and still do!) it was only on special occasions such as birthdays and maybe at Christmas. Many working class people joined a Christmas club where you saved money regularly to help with the expense at Christmas time. You had to borrow from the club during the year but you paid interest on the loan which all went into the club so at Christmas you always got a little bit more out than you had paid in.

Next door was another general store of sorts that sold dry goods and sweets in open boxes on the counter. The cash register was against the back wall so when the owner, Mrs Palmer, turned to use that cash register, she was often relieved of a little of her stock! One day I got caught redhanded; it was so embarrassing; needless to say I did not try anything like that again! The shop is now the Post Office and sells groceries and stationary etc.

In 1954 two additional shops were built next to these two shops, one was a butchers (the butchers in Gravel Lane had closed earlier) and the other a greengrocers. When the Butchers had to close it reopened as a Chinese takeaway; and when Eve the owner of the green grocery shop retired, she couldn’t sell it on as a greengrocery business, so it became an Indian takeaway. A sign of the times we live in. Rather sad really!

Memorial seat at Roe's Well

Jack Sheppard and his old mother ran a greengrocers shop of sorts, with veg. and fruit sold from the scullery at the back of their house; an early Victorian detached brick house next door to Palmers shop. (It was where Raymond Way is now!) He was quite a character, if he didn’t like the look of you, he wouldn’t serve you! When I was in there at one time, a lady, who I didn’t recognise, asked for tomatoes, but Jack said; “Haven’t got any.” in his usual brusque manner, but he had got tomatoes; at the time I thought it very strange, it defied logic turning down a sale; there was no doubt about it he was an odd fellow!

Behind his house he kept a lot of chickens, ducks and turkeys, keeping them in with a spring loaded rickety gate that had a bell hanging on it. It bounced up and down when you opened the gate; loudly heralding your arrival. I never like going in there as his cockerel would go for you if it heard or saw you. Wings out and head down it would even go for Jack; he would kick out and shout at it to no avail, it wasn’t easily deterred! (It wasn’t there after Christmas!) Any excess vegetables Dad had from his allotment he sold to Jack. Dad’s first allotment was on the site adjacent to the forest where the Sunnymede houses are now.

Further along was a row of four of the oldest wooden houses in Chigwell Row. Sam Pead lived in one with his daughter Ethel. Sam always had an old pipe stuck in his mouth; with his white hair and beard and a small dog in tow, he was quite a character. Ethel never married and worked as a cleaner at the church.When the houses were built at ‘Sunnymede’ on the allotments alongside the forest, they were moved to a new site below the Retreat public house. Houses were again built on the allotment site becoming Sylvan Way and the allotments moved to a site in Gravel Lane.

We even had our own boot and shoe mender, Mr Dave Williams, who did the repairs at his home at No 2 Dove Cottages, off Gravel Lane. When I dropped our shoes off to be repaired he would always be the one to answer the door, his wife was very timid and used to hover in the background! He always delivered the repaired shoes or boots back to you on foot in a white sack slung over his shoulder. Dad used to do some of our repairs using Phillips stick-a-soles but they didn’t seem to last very long before they came unstuck! ‘Blakeys’, small half moon shaped studs, were hammered into the toes and heels of the shoes but they didn’t seem to last very long either! Woolworth’s shop in Barkingside used to sell all the DIY shoe repair materials. Their large shops were advertised as the ‘thrup-penny and sixpenny’ stores in the 1930’s and affectionately called ‘Woolies’. Most of their merchandise was either 3d or 6d! They sold a wide range of products; toys, clothing, sweets, small tools etc. etc. All the Woolworth’s stores closed many years ago.

F. Harman & Sons were the Builders Merchants and Undertakers; down by the side of and behind Reads Sweet shop. They were cabinet makers as well, even making the coffins they used in their undertaking business in the early days. They did much of the building work and repairs, including the decorating, throughout the village. For some obscure reason they also sold Paraffin! The two sons, Phil and George ran the business after Frank their father and founder of the business died. George had an artificial leg. Dad said he had lost his leg in a motor cycle accident. They always walked to the job where they were working, pulling a shallow cart with two large wheels and a ‘T’ shaped handle. All the tools and building materials they needed were carried on the cart. They never progressed to motorised transport.

Oaklands Farm, next to the Builders Merchants, became a Girl Guides camping ground in 1935. An outdoor swimming pool complete with changing rooms and diving boards etc, was built for the Guides to use. The local people could use the pool when the Guides were not in residence. It was opened for us to use during the war and for quite a few years after. I can’t remember exactly how much it was, but I think it would have only been about thrup-pence or sixpence. (About 1p or 2½ p) In 2016 it closed as a Girl Guides camping ground.

Not surprisingly we also had a barber in the village – Mr Rix. He operated from a very small caravan in his garden at the side of his house, a semi-detached Victorian wooden cottage opposite the garage. Without electricity he used hand clippers and wasn’t all that careful; having your haircut was a painful experience. I think it cost just, 1/6 (7½ pence).

Site of Mr Spain's forge. Picture 2018

The Village blacksmith was next to the Garage with its single petrol pump. Albert Spain was the blacksmith; I used to be fascinated watching him shoe the horses. He would pump the bellows to heat the iron until it was red hot in the coke fire and then hammer the shoes to fit in a shower of sparks on his anvil before eventually nailing it to the horse’s hoof. The horses seemed so patient as he removed the old shoes and put the hot new one on the hoof in a cloud of smoke and smell of burning hoof. Dad used to collect the hoof clippings and the droppings from the horses for his allotment. Albert Spain was a Chapel man and is buried there. He had a house built right opposite his forge and moved into it in about 1936/7. His ‘forge’ building and house are still there; after Mr Spain’s death the ‘forge’ was taken away and the building used to manufacture Garden ornaments and statuary for many years. Now it’s a business that sells and repairs garden machinery.

A well established hackney carriage business was carried on from Scotts Cottages by Eddie Green. (A rather large Eddie was addicted to ‘Cowboy’s and Indian’s’ films on his B&W television!) I remember that he had an Austin 12, it was quite a large car actually, later he had a Buick. His father, ‘Brock’ Green used a horse and trap, but I don’t remember him. He used to meet the trains in his horse and trap at the recently opened Grange Hill station early in the 20th century. This was well before they had motor cars.

One Sunday morning Eddie was outside the church waiting for his ‘fare’ to leave church, before driving her home. While he was waiting and standing by the gate, many people that he knew would be leaving church after Morning Service (and he knew nearly everyone!) He would greet each one with; “G’mornin’ Mrs So & So…. “Cold ‘ole morning!” To hear him repeat this simple observation to each person he knew, was quite amusing.

There always seemed to be various tradesmen calling. There was a Mr Bush who sold fruit and vegetables from the back of a horse and cart. (Or it may have been a lorry!) Not that we bought much as Dad had his allotment, so we were almost self sufficient in potatoes and veg. Mr and Mrs Hadyn from Woodford Bridge, and later their daughter in law, had a small van selling hardware and I think dry goods and groceries. Their son used to go to the Isle of Man and take part in the annual motor cycle races that were held there. There was, of course Mr Brighty from Abridge, who exchanged our accumulator every week for a fully charged one for 7d a week, to use in our wireless. On one occasion, when I was very young, I can just remember a gypsy calling on us selling clothes pegs that they had made. Another time when they called, I remember they were trying to sell us ‘lucky’ sprigs of heather. But Mum would have none of it.

The newly built ‘State’ cinema at Barkingside was our nearest picture house, where a couple of the first films I ever saw starred Shirley Temple, although I can’t remember too much about them, but I do remember her tight curly hair and her singing the song, ‘On the Good Ship Lollipop’, It was a popular song at the time, it came from the 1934 Hollywood film, ‘Bright Eyes’. In about 1937 I saw a Disney film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs I was taken there by Mrs Haddon with her daughter Margery; they were our neighbours from Grove cottages.

On another occasion, my friend Noel’s father took us both to the ‘State’ cinema to see the 1930’s American war film, ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ we saw that in about 1936, I’d guess. I would have been quite young as the story eludes me; I have no memory of it only the trench warfare and the fighting come to mind. I think I was just too young to fully understand the story line. The film was based on Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel of the same name. It was a human story about the horrors of the First World War.

The pond in the field behind our house

The fields behind our house were my playground; everyday after school I would go into the fields on my own or with a school friend; at first it was Roy Ashbridge from Chase Farm, then Noel King and later it was Derek Bateson. Roy lived in a wooden cottage at Chase farm from where we would cross a field to visit his Gran in Bennetts Cottages in Gravel Lane. She always gave us each a slice of bread and jam when we visited! The Horse Chestnut tree that was in her front garden is still there and the tall Elm trees that were along the road opposite hosted a rookery; but the trees have long gone having succumbed to Dutch elm disease in the 1960’s. Noel King and his three sisters lived in Chapel Lane; the next Lane to Grove Lane where I lived.

A bit later on Roy had a ‘Diana’ air gun and wanted Noel and me to attack him with clods of earth and other missiles while he was perched up in a Willow tree by a nearby pond. He said he would defend himself by taking pot shots at us with his air gun! Needless to say we declined to play this game. What if one of us got a pellet in the eye? Perhaps subconsciously we were remembering that Roy’s Dad had a glass eye. That eye never moved which gave him a slightly strange appearance when he looked at you. How he came to lose his eye I have no idea (his eye before he got the glass one! As far as I know he never lost his glass eye.) Roy always was a bit of a maverick and a dare devil. He was absolutely fearless especially when climbing trees!

During the school holidays Noel and I would sometimes meet up with George Chichester the son of Francis Chichester* (of nautical fame) from his first marriage. I felt sorry for George, because he was asthmatic and didn’t seem to have much of a family life either, and he appeared somewhat lonely and largely ignored by his father and stepmother. Francis Chichester did not have much time for us children either, for although we bumped into him from time to time, I cannot remember him ever speaking directly to us! The family lived throughout the war in ‘Pages’, a small Georgian detached house in Chapel Lane. Years later I read in the Sunday Express newspaper that George Chichester had died in Australia working as a waiter. Later Sir Francis Chichester had another son, Giles, by his second wife; Giles became a Member of the European Parliament.

Noel lived in one of the two 17th century cottages opposite ‘Pages’ with his parents and three sisters. His mother was a genteel lady, a complete opposite to her husband who I remember as being rather coarse. He told Noel and me a little rhyme that I still remember to this day, perhaps because it was rather ‘risqué’ for 7 or 8 year olds. It went like this;‘I chased a bug around a tree; I’ll have his blood he knows I will’ (say it quickly!)

Mostly we would just roam around the fields or play around the numerous ponds, building damns or dens, or fishing for sticklebacks, and in the spring, bird nesting. We would be gone for hours but our parents never seemed to worry too much about us, where we were or what we were up to. Children were quite safe on their own in those days.

A favourite den making material was the fast growing Elder stems, they were very straight and easy to break off and manipulate. Boys, especially country boys seem to have an instinct to want to build a shelter or den of some sort; no doubt needed as protection from the elements in Stone Age times! The ‘spring fed’ ponds would have watered Chase Farms cattle before 1940, that is, until the farm was turned over to agriculture; ordered to by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries soon after the war started, but the ponds remained. Every pond always had a single pair of Moorhens nesting on it and sometimes, if there was a suitable tree near the pond, a pair of Mallard ducks would nest there too. Mallard nest in shallow holes in trees close to water. We quickly learned to respect the water after one or two slips in and wet feet! Nowadays parents are paranoid about ponds but there were no fatalities among us boys that I knew of. I remember one incident during the winter when I was on my own and checking the ice on the pond that was closest to our house. It wasn’t much of a pond as it had silted up somewhat over the years, but I decided to test the ice by jumping on to it and went through, filling both wellingtons with ice cold water. The problem as far as I was concerned was how to explain the wet socks and wellingtons to my mother! When I plucked up courage to return home, my luck was in and my mother was out; so I wrung out my socks as best as I could and put them on the top door of the Kitchener’s fire grate to dry, a big mistake as I succeeded in burning the sole out of one sock and severely burning the other. I continued to wear them like that for the rest of the week, and it was a very uncomfortable. It was when they had to be changed my mother discovered the large holes. As a way of explanation I lamely said I did it warming my feet in front of the Kitchener! Much to my astonishment, she swallowed this excuse. For some reason, it hadn’t occurred to her that I would have burnt my feet as well!

Because we had the Kitchener and sometimes an open fire in the front room that needed wood, Mum, Dad and me would go ‘wooding’ in the autumn, mostly down those fields behind our house or sometimes in the forest behind the recreation ground. We would take hessian sacks to collect any faggots, sticks or fallen branches etc. that we could find; in fact any wood that would burn was collected or dragged home and sawn up to put in our coal shed ready for use in the winter. Another annual late summer and autumn ritual was picking blackberries and collecting fallen crab apples when we could find them. A lot of people picked blackberries in those days so you had to be quick to get the best crop. Knowing where to pick blackberries in places that were less frequented by others was an advantage. ‘High Woods’ was a scrubby area several fields away but it had a lot of blackberries, Dad carried a walking stick so that he could pull down those branches that were out of reach as they usually had the largest and juiciest berries! As we didn’t have a fridge or freezer the blackberries had to be eaten or cooked or bottled in Kilner jars or even made into jam within a few days of picking. Mother made all her jams from various fruits when they were in season including crab apple jelly. Wine making from elder berries and other fruits was made by Dad; he always said his parsnip wine tasted like whisky but I was never allowed to try it! Not that I would have known what whisky tasted like. I remember seeing yeast spread on to a piece of toast floating on top of the liquid (Boiled fruit with sugar added.) and a damp cloth draped over it while it was fermenting.